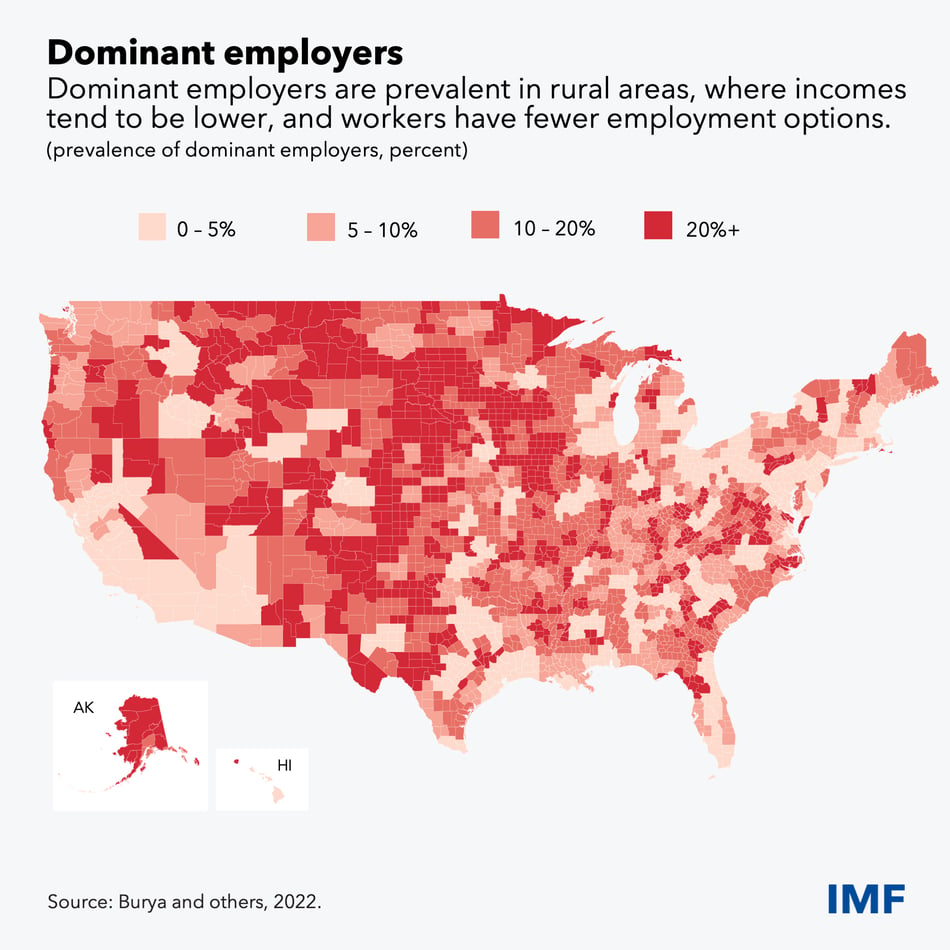

Some employers can attract a large pool of job applicants without having to offer higher wages. We call such employers with significant labor market power dominant, and they’re prevalent in many parts of the United States, especially rural areas.

Dominant employers are much more likely to respond to rising interest rates by firing workers because they can more easily hire back when the Federal Reserve starts lowering interest rates, our new research shows. Less educated workers in poorer regions tend to be most affected because dominant employers are relatively more prevalent in poorer regions.

These findings are especially important amid the fastest interest rate increases in a generation. Elevated inflation is prompting the Fed to act, which will affect employment as businesses reduce investment and payrolls and consumers spend less. In this period of rapid inflation, Fed tightening is appropriate in pursuit of its dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability.

Our work suggests that the unemployment rate—which recently reached a half-century low— is now likely to rise, in part because of the role that dominant employers play in the US. And that in turn would exacerbate inequalities between regions.

Defining dominant employers

Our study relies on data from Lightcast, formerly Burning Glass Technologies Inc., a major provider of real-time US labor market data.

To create a new definition of dominant employers, we use the share of vacancies controlled by any given employer in US regional labor markets. Dominant companies typically account for almost 10 percent of open positions in their regional market.

The data also shows that dominant employers are mostly located in less densely populated areas of the US, especially in rural areas, where incomes tend to be lower and job-seekers have fewer employers to choose from. Dominant employers are disproportionately in industries like healthcare, agriculture, and mining.

Having defined dominant employers, we study how their hiring decisions have varied in response to monetary policy surprises—unexpected interest rate hikes or cuts—over the last 10 years.

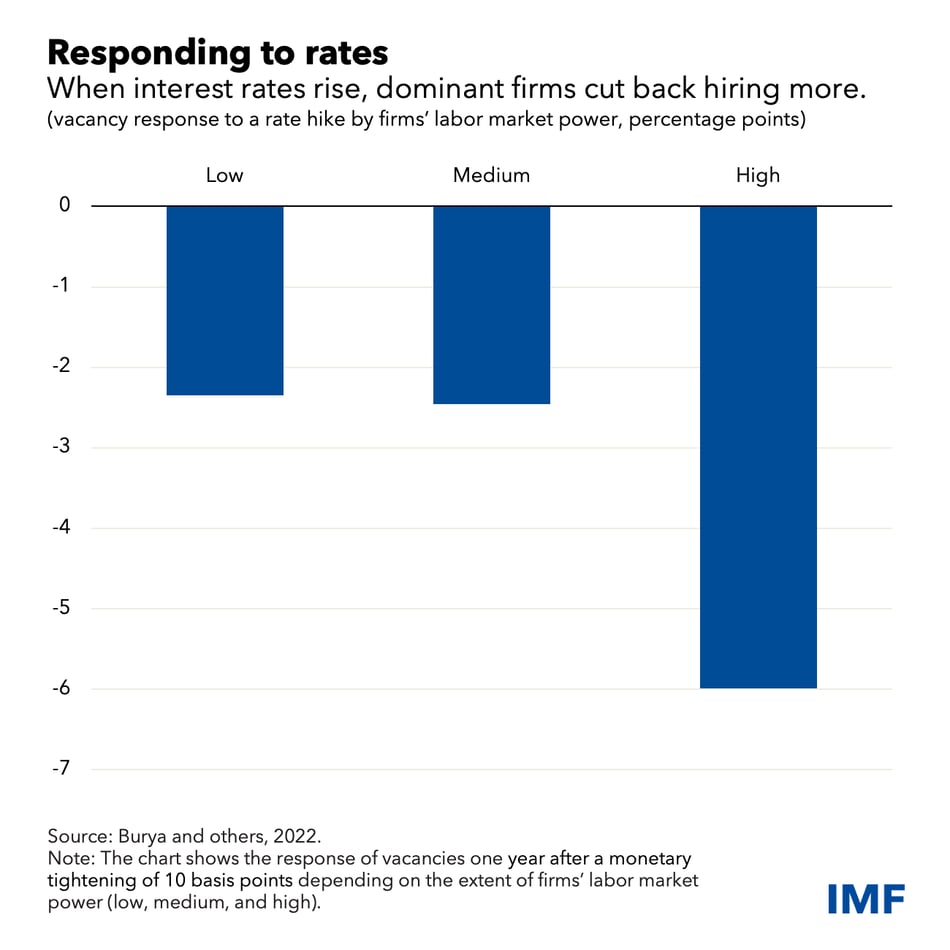

The analysis shows that dominant employers are more responsive to changing interest rates—they cut back on vacancies much more when rates are rising relative to other employers. Using firm-level data, we confirm that fewer vacancies in turn reduce employment. These effects are particularly important for less educated workers and those with limited IT skills because they cannot easily find new jobs. On the other hand, the analysis shows that all employers cut wages when interest rates are rising, and dominant employers are not different in this regard from other employers.

Why would dominant employers fire workers when interest rates go up? When interest rates rise, demand for products declines, production costs rise, and the need for workers is reduced. Because dominant employers can usually hire more easily, they are more likely to fire staff.

Implications for taming high inflation

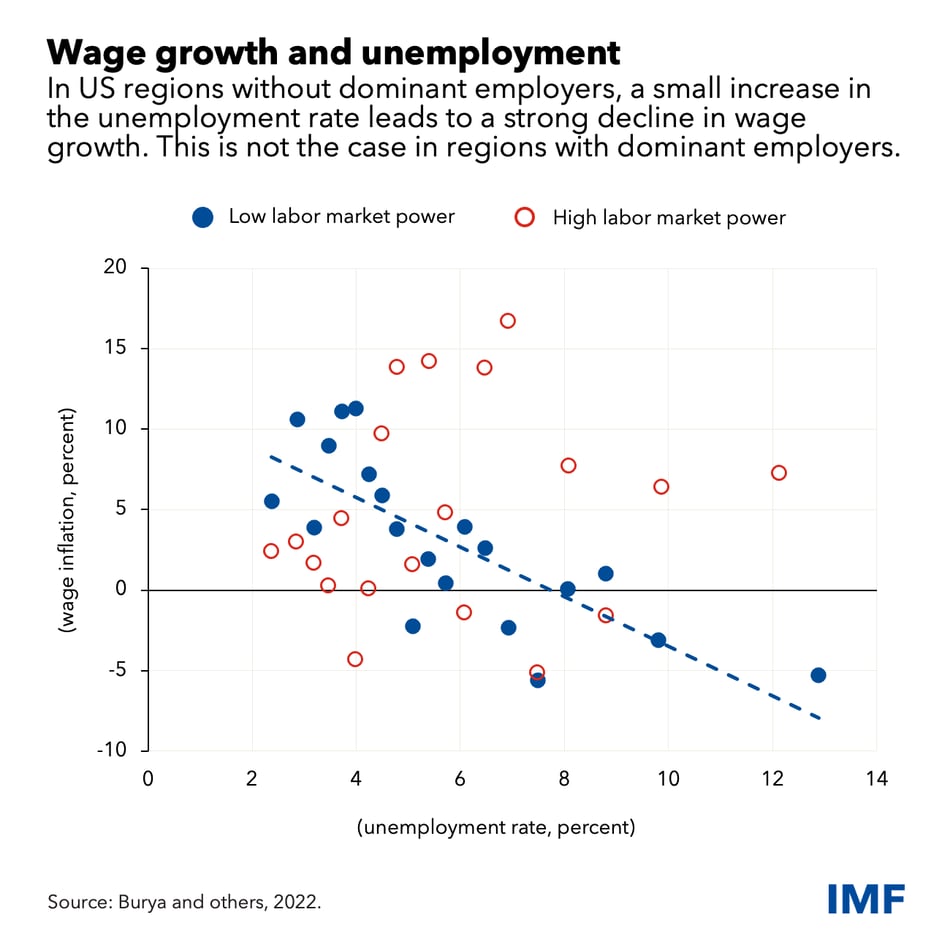

To bring down inflation, the Fed needs to raise interest rates. It is, however, difficult to do so without creating higher unemployment. Historically, small increases in the jobless rate have reduced wage and price pressures significantly, but more recently, this relationship has weakened.

Our findings point to an important role dominant employers play in this weakening. In regions less likely to have dominant employers or those with low labor market power, even a small increase in the unemployment rate leads to a strong decline in wage growth. However, this is not the case in regions where employers have high market power – dominant employers don’t need to reduce wages because they cut costs by firing workers. In regions with dominant employers, jobless rates increase significantly more as interest rates rise.

Since regions with dominant employers tend to be poorer to begin with, rising interest rates will push unemployment up exactly where incomes are lowest. This mechanism would thus lead to an increase in inequality across and within regions as the Fed raises interest rates.